This week’s Tidy Tuesday deals with data about Himalayan climbing expeditions. Alex Cookson, who cleaned and shared this data from the Himalayan Database, wrote a two-part blog post exploring this data. The second part of this post looks at Everest expeditions and the dangers faced by climbers there. In the conclusion to the post, he notes a few other questions that could be explored using this data, namely:

- What is the composition of expeditions? For example, how big do they tend to be and what proportion consist of hired staff?

- What injuries are associated with climbing Everest?

- Are there characteristics of climbers associated with higher or lower death rates? For example, are Sherpas – presumably well-acclimated to high altitudes – less likely to suffer from AMS?

- What are the general trends in solo expeditions and the use of oxygen?

In this post, I will explore each of these questions in turn.

Expedition Composition

First up, “What is the composition of expeditions? For example, how big do they tend to be and what proportion consist of hired staff?

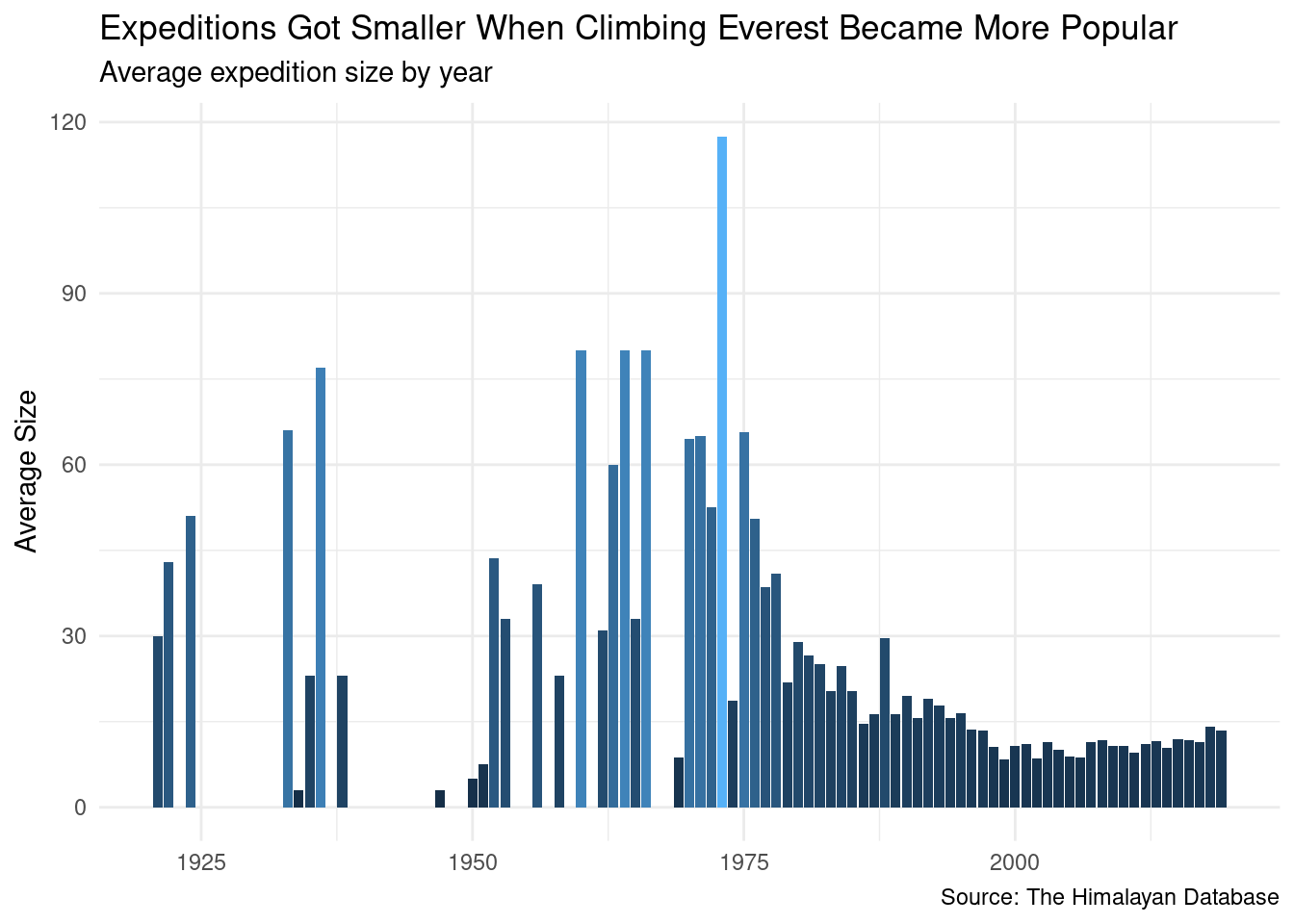

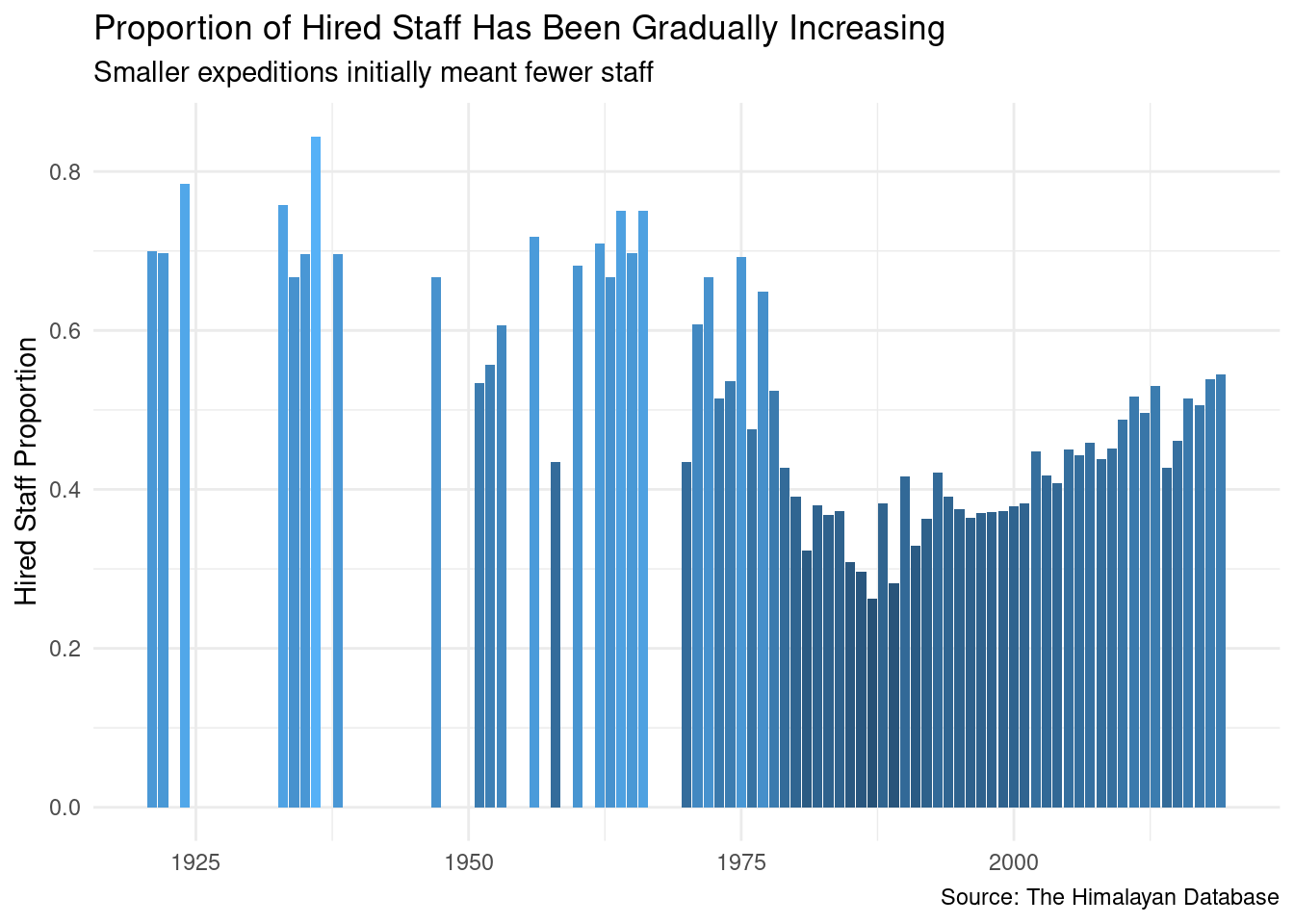

As climbing Everest became more popular, expedition size shrunk and then stayed small.

Smaller expeditions initially meant a lower proportion of hired staff, but this proportion has been gradually increasing over the last several decades.

Injuries

Now let’s turn to the injuries that are associated with climbing Everest.

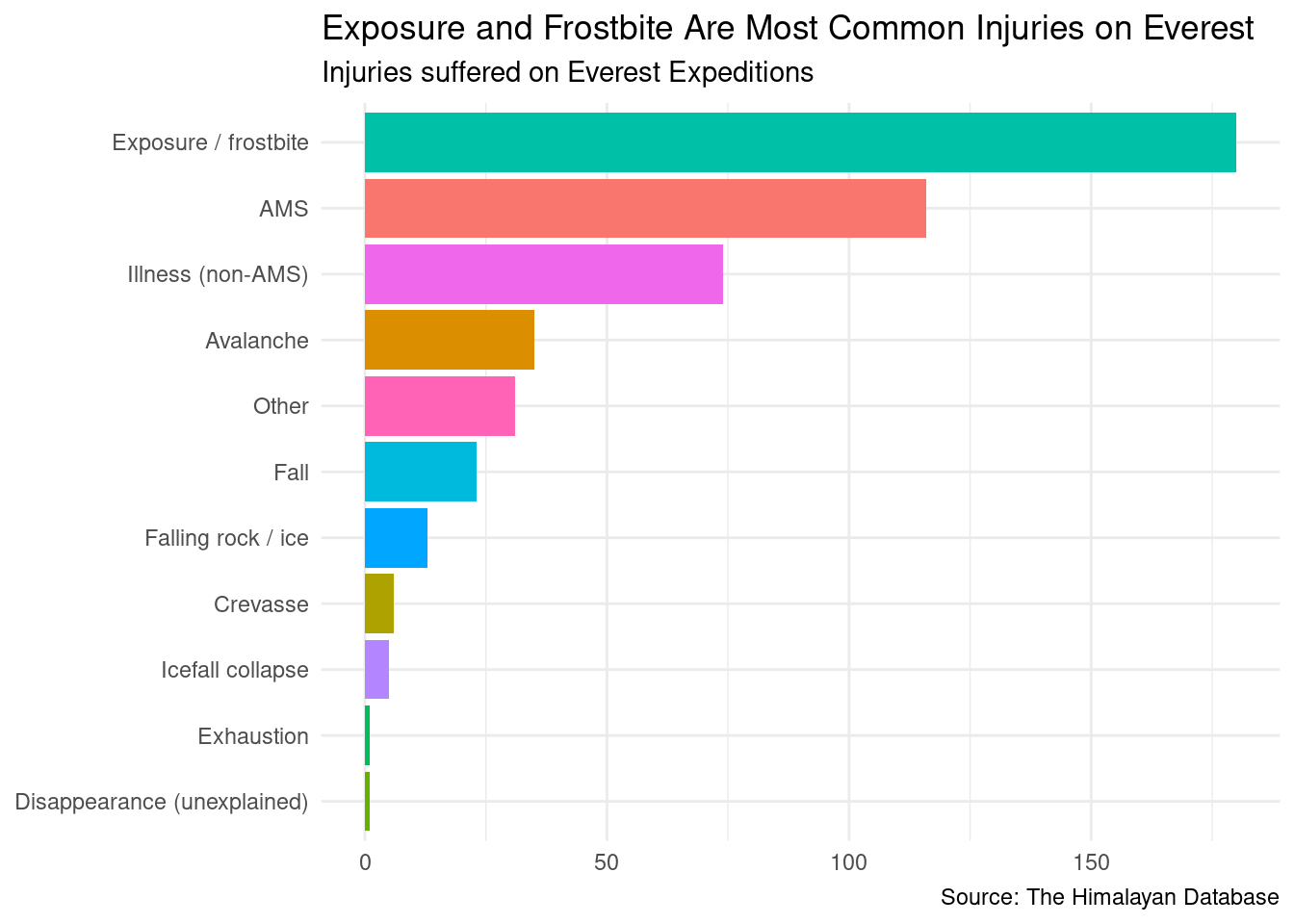

There are many perils associated with climbing on Everest, but exposure and frostbite are the most common, followed by AMS (altitude sickness).

Altitude Sickness

Cookson’s next question is, “Are there characteristics of climbers associated with higher or lower death rates? For example, are Sherpas – presumably well-acclimated to high altitudes – less likely to suffer from AMS?” Let’s look at his example question in particular.

Sherpas are members of an ethnic group indigenous to the mountainous regions of Nepal and neighboring countries. Because of their prominence in mountaineering work, the term “Sherpa” is used by climbers to mean any local guide or hired staff regardless of ethnicity. According to this data set, the overwhelming majority of hired staff on Himalayan climbing expeditions are citizens of Nepal, and only a handful are citizens of countries other than Nepal, China, or India. Therefore it seems appropriate to consider “hired staff” as a stand-in for “Sherpa” when exploring these data.

Climbing the highest mountain in the world is dangerous. It’s also extraordinarily expensive and time consuming. Climbers who die on Everest made a choice to take on this risk and while their deaths are tragic, these climbers made an informed choice to take on the risk. The same cannot be said for their hired staff. Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world, and mountaineering work pays well by local standards. Whether this sort of tourism is a net benefit for these communities and their country is a complex question, but their deaths are one of the many morbid symptoms of global inequality.

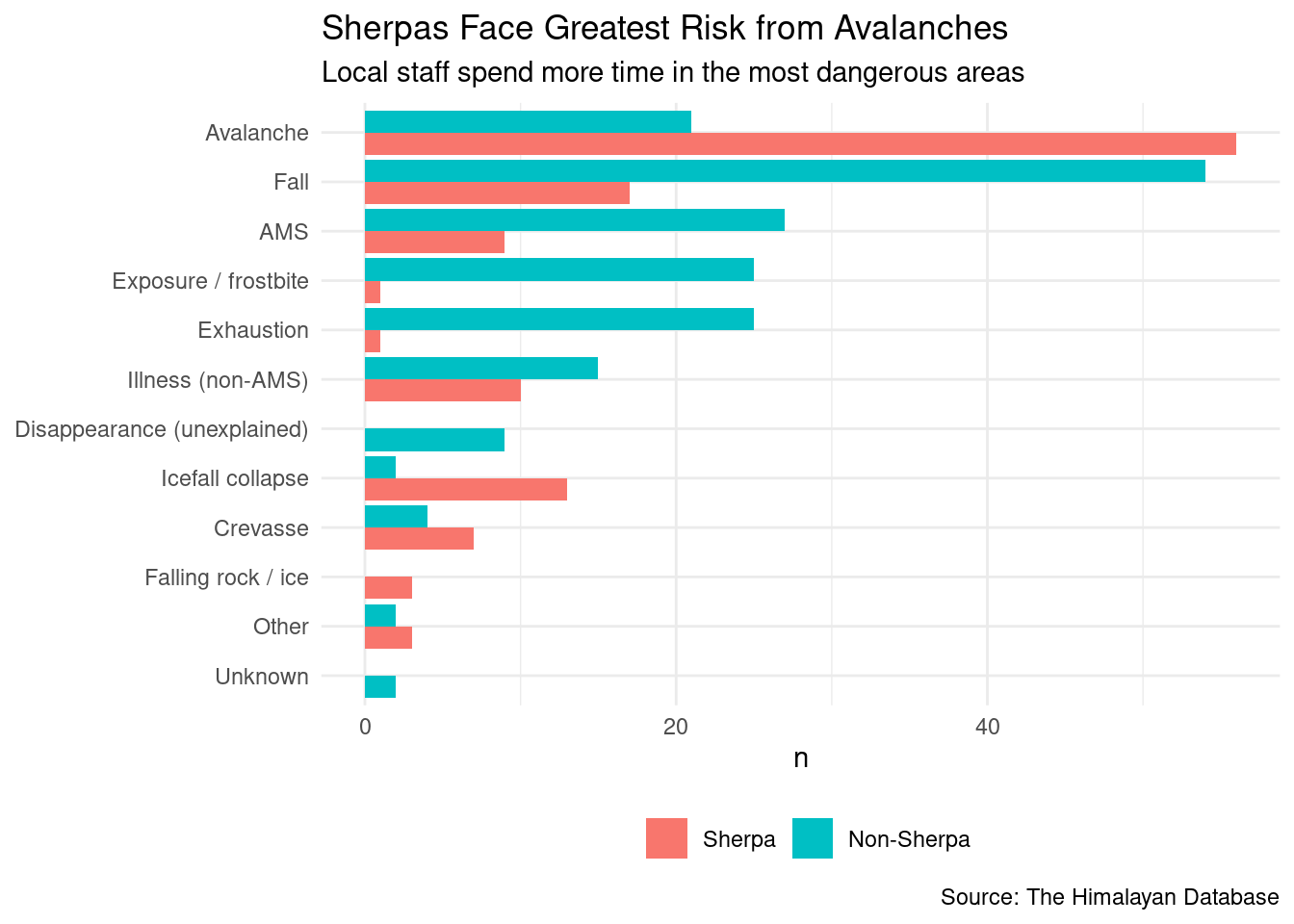

Additionally, Sherpas face greater risk than their clients, which can be seen in the causes of death.

So among deaths on Everest, Sherpas, who are required to spend much more time in dangerous zones, are much more likely to die in avalanches while non-Sherpas, who are presumably less well acclimated to the altitude, seem to face a greater risk of AMS.

Out of 120 Sherpa deaths on Everest, 56 (46.7%) died in avalanches while 9 (7.5%) died from AMS.

Out of 186 non-Sherpa deaths, 27 (14.5%) died from AMS. The most common cause of death for non-Sherpas was falling. 54 of these climbers (29%) died from falls.

However, if we look at causes of death in terms of total number of climbers, then the risk of death from altitude sickness is similar for Sherpas and non-Sherpas. 0.18% of non-Sherpas died from AMS compared to 0.13% of Sherpas. Sherpas may benefit somewhat from better acclimation to the altitude, but they still face a similar level of risk for dying from altitude sickness.

The more significant story here is the much greater risk Sherpas face of dying in an avalanche. Work such as establishing routes and carrying supplies means that Sherpas spend more time in avalanche-prone areas then the recreational climbers they are supporting. They take on this risk for their wealthier, whiter clientele, and sometimes they pay for it with their lives.

Solo Expeditions and Oxygen Use

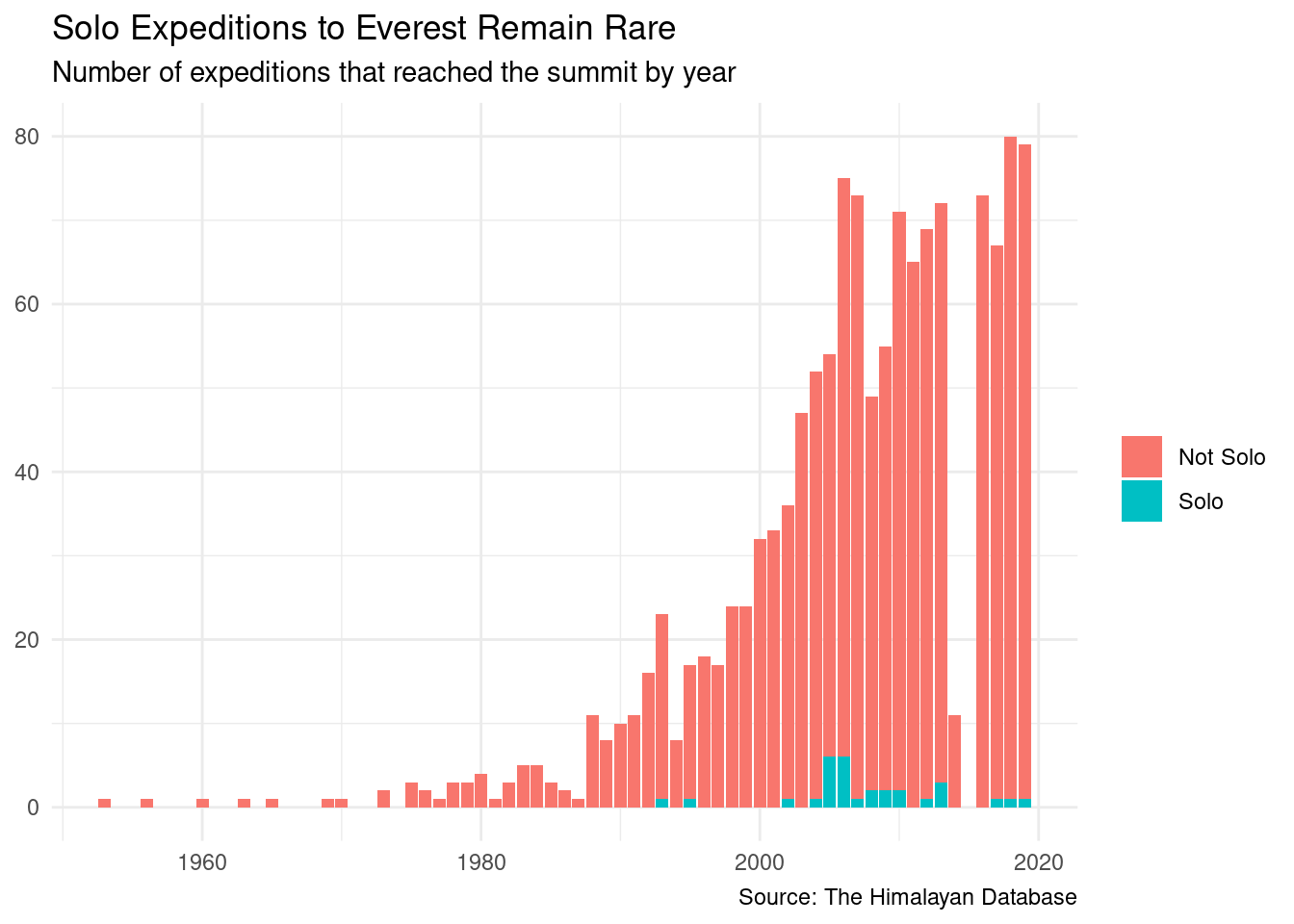

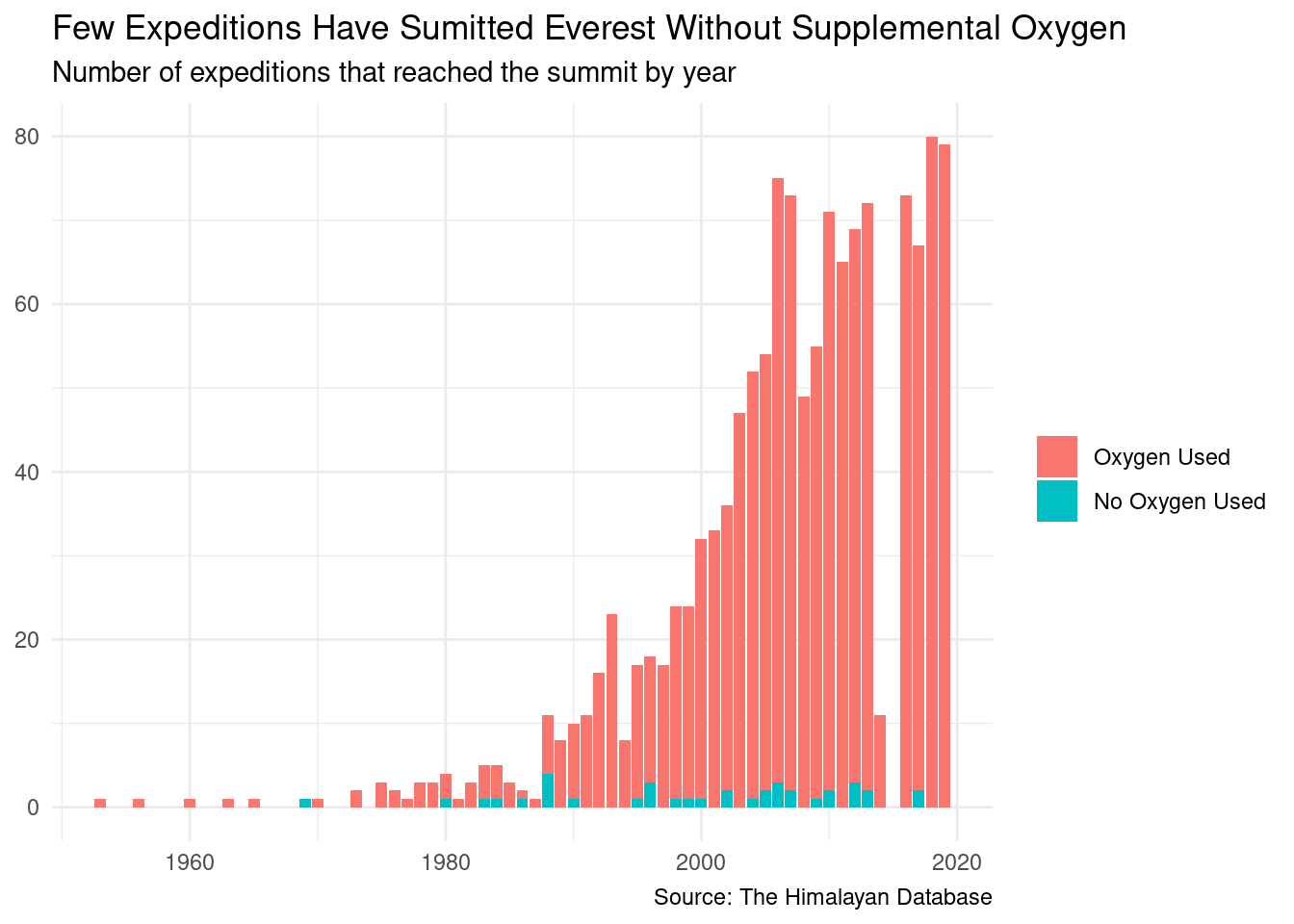

Now let’s take a look at “the general trends in solo expeditions and the use of oxygen.”

2005 and 2006 saw a peak in successful solo expeditions, but they remain rare.

Trips to the summit of Everest have overwhelmingly involved the use of supplemental oxygen.

That’s all for now. Take a look at my code on GitHub.